كيف يمكنك العثور على محتوى باللغة الإنجليزية على موقع عربي؟

Unless you are an Arabic speaker, that heading is probably mystifying. For the more than 25 million people in the U.S. with Limited English Proficiency (LEP), a lot of information online can be just as confusing. Many federal government web teams are working hard to help by creating content in multiple languages. These translations will help people find information to help them pay their taxes, secure benefits, and respond in emergencies. But what if the people that need this translated content the most can't even find the content in their language?

This is what the 10x team sought to explore.

Our colleagues at the U.S. Census teed up an interesting question: how can we design a language selector that helps people who don't speak or read English find content on government sites? Most design conventions for language selection are based on e-comm models. Do we need a different approach for information-rich sites and apps? 10x agreed this problem was important and set out to research how monolingual speakers find translated content on government sites — and how the design of a language selector can help them find it more easily. To do this, 10x conducted research with monolingual speakers of Spanish, Arabic, and Mandarin Chinese.

10x's research built on the good work done by the Multilingual Community of Practice and the U.S. Web Design System(USWDS) team. The goal of the research was to understand how best to help monolingual users find content in their preferred language on government sites. Monolingual users are an important audience for content in languages other than English, but by no means the only audience. 10x's research only focused on people with little or no English language skill.

Web teams have been working hard to help people with LEP navigate public health emergencies, immigration challenges, and an increase in the frequency of natural disasters. Even so, there is the need for better and more uniform translation of information around health, public safety, unemployment, and government benefits. Providing a clear and easy way for the public to find content on the site is foundational to this effort. Content in preferred languages is not helpful if people cannot find it.

Language access is a civil rights issue, an equity issue, and an inclusivity issue. Language access requirements in federal programs and services originate from Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and have been addressed in numerous subsequent acts and Executive Orders. Executive Order 13166 was signed on August 11, 2000, to improve access to government services for people with Limited English Proficiency (LEP). In addition, the President's Management Agenda (PMA) Priority 2 focuses on delivering excellent, equitable, and secure federal services and customer experience (CX). Civil servants all over the federal government are working hard to meet the needs of all the people.

Interviewing members of this population reinforced how much they need quality translated content — and how challenging they are to serve. This population is often vulnerable and building trust with each participant is critical to ensuring good feedback. See the Methodology and process section for information on how we identified and built trust with test participants.

We hope this research will help inform discussions about improving language access.

How monolingual LEP users start their journey

Factors influencing online behavior

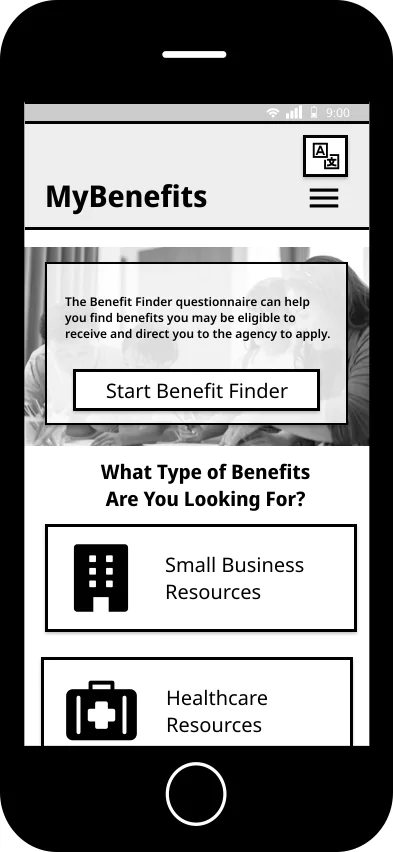

Test participants rely heavily on mobile devices, and for many it is the only way they access the internet. For example, while 56% of Mandarin speakers have used a computer for complex tasks (usually borrowed and with assistance from others), 44% use phones exclusively. Even for those who have used computers, their mobile device is the primary way they access the internet.

Many of the participants have very low technology literacy and are not comfortable exploring websites and apps and do not own their own computers.

"I don't even know how to turn on a computer and when I need help filling out a form I ask my daughter to do it for me."

In addition, many of the participants have older model phones and use prepaid plans. Many do not have Wi-Fi at home, including, for example, about 90% of the Spanish-language participants.

Family and friends play an important role in participants' use of the internet. Almost all participants reported that they look to family and friends for advice on which websites to use and for help completing more complex tasks. For many non-English speakers, they rely on children, friends, and community members to help them find and understand digital information.

Mandarin participants reported that in-person or phone services were preferred because Chinese-speaking agents or translators were often available.

How users start their search

Test participants mentioned needing information on immigration and citizenship processes, benefits eligibility, and crisis response. They generally start their search on Google or another search engine (Baidu was specifically mentioned by Mandarin Chinese speakers). Mandarin speakers, for example, start their search on a search engine or by accessing websites via links provided by friends and family. Six of 16 participants searched in Chinese exclusively and 10 of 16 searched in a combination of English and Chinese.

"Because my English isn't very good, so sometimes I'm afraid I'll write the keywords incorrectly and it won't find anything."

Search results are generally in both Chinese and English, though some participants only click on Chinese-language links.

Spanish speakers specifically noted that they rely on search results in Spanish.

"I only select search results that provide information in Spanish, so I don't have to dig for links or wonder what I should do once I arrive at a site."

Automated translations

Test participants also rely heavily on automated translations, especially Google Translate, though how they use it depends on their technology skills and English proficiency. Despite automated translations being so heavily used, participants indicated that the translations are often poor quality and difficult to understand.

"[T]ranslate" for me can mean providing an instant translation rather than translated content. I find the former to be of less credibility for me to find content I can rely on in my native language."

All participants relied on automated translations to some degree. Participants reported:

- Using browser features to translate an entire page.

- Taking photos of pages and using translation apps to translate the text on the image.

- Copying text from web pages and pasting into translation tools.

Participants also noted that auto-translations did not translate everything on the site, including dropdowns.

.gov as an indicator of authority and reliability

Test participants search for content by topic, not by organization. So users looking for information on immigration might search for "Tarjeta verde" (or "green card"), not for USCIS or U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Arabic-speaking test participants were the only participants that reported actively looking for .gov sites. None of the Spanish- or Mandarin-speaking participants used .gov to assess the credibility of the content.

The role of social media

Many participants indicated that they often search YouTube, Instagram, or TikTok for information in their preferred language. Spanish-language participants, for example, reported looking for guidance and how-to information on immigration and government benefits. In lieu of good indicators for content quality and accuracy, they used other indicators for perceived authority, such as titles (for example, lawyers) and production quality of the videos.

"I was seeking assistance with my immigration situation and searched YouTube for a lawyer. I found several who explained the steps, requirements, and how to contact them."

On-page behavior

Language selector

All participants look for a language selector in the upper right. This was true for many Arabic participants, even though most Arabic-first sites put the language selector in the upper left. Participants did not distinguish between placement in the nav or utility sections. They just looked in the upper right.

Most participants recognized the word "Languages." For Mandarin participants, for example, 75% recognized "Languages," and understood it to mean that the content it links to is translated by humans. The term "Translate" was generally understood to mean automated translations, such as Google Translate.

"When I look at a button with that word [Translate], I think the website will do Google Translate."

Arabic-speaking test participants were the exception. They were not as familiar with the term "Languages," and preferred Arabi عربي or the alternative العربية.

Familiarity with technology played a role here, too. Some of the Mandarin Chinese test participants, for example, knew to look for information in the mobile menu ("hamburger" menu), but not everyone did.

Dropdown indicator

Even if they understood the label "Languages," participants did not always know what behavior to expect when they clicked on the button. They expected it to take them to translations, but were not sure if it would open another page. Participants, especially Mandarin speakers, felt that a dropdown indicator (arrow) would make the label clearer.

Iconography

Icons alone were not effective language selector indicators.

None of the Mandarin participants, for example, knew what the globe icon meant. 95% of the Spanish-language participants did not interpret the globe as a link to Spanish content. Some believed it meant "countries" or "network." Symbols commonly used to represent language selection are understood differently across cultures.

"It might be a link to the web or Google Translate, but I really don't know what it is. My old mobile phone doesn't always show graphics from a website."

One user pointed out another problem with relying solely on an icon:

"There's another problem: If it's in text form, I can use a translator to translate it. But I don't know how to translate this icon."

That said, test participants agreed that an icon made the button more noticeable, and often recommended it be paired with the word "Languages."

![]()

Animated language selector

Most participants found that an animated language selector was significantly more noticeable than a static one, but many found it distracting. Some didn't understand what behavior to expect from it. For example, some felt they had to "wait for their language to come around again," and then click on it.

"That button really caught my attention. It was the first thing I noticed. I just wonder what happens when I miss clicking on the Spanish link?"

In-page notifications

Participants generally did not expect to see in-page language options and did not scroll the page looking for links. They expected to see their language options at the top of the page. When Mandarin participants saw an in-page language option, they believed that it only translated that specific section.

"You know, because I always use my mobile phone, I never think to scroll to the bottom and look for a link to Spanish content."

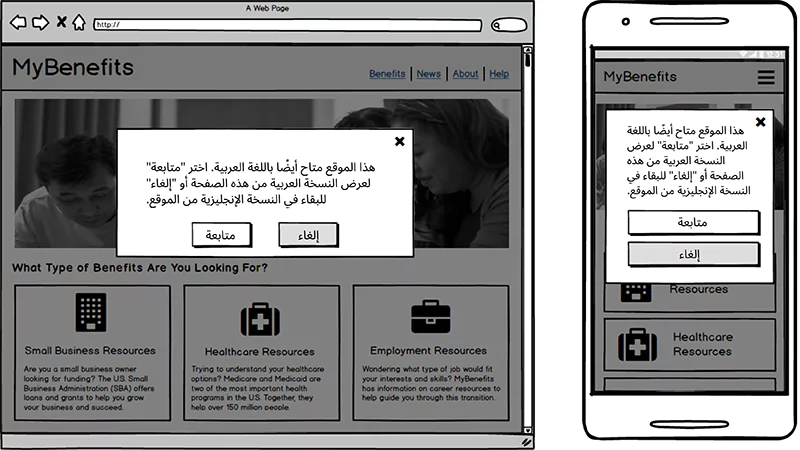

Pop-up notifications

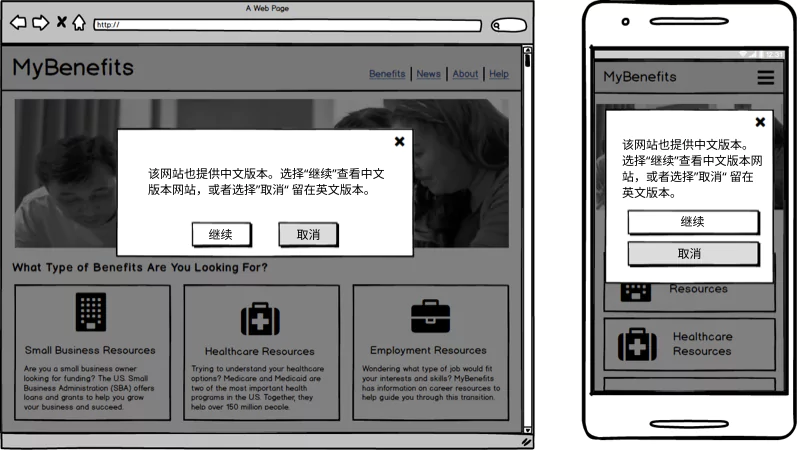

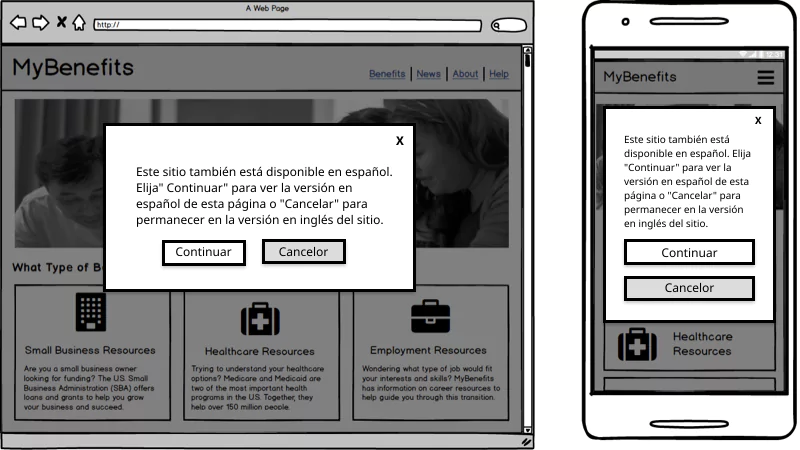

Participants generally reacted negatively to alerts letting them know that their preferred language was available. (A few Arabic-speaking participants did appreciate the option.) They viewed pop-ups as associated with ads and scams, and language notifications were not a pattern they were familiar with. Alerts feel disruptive and participants prefer to be in control of their experience.

Search

Spanish-language user testing participants reported that they look to Search to help if they don't see a language indicator.

"Whenever I need information from a specific website that does not have a link to Spanish content, I use the search box to look for it. If the site has it [Spanish-language content], it will appear in my results."

Challenges

Currentness and accuracy

When monolingual users do try to use content in their preferred language, they often find that it is inaccurate or hard to understand. A couple of the Arabic-speaking test participants noted that they had been denied specific benefits due to outdated or inaccurate information.

"When I arrived at the bus station, I found out that the Spanish version of the agency's website was not as current as the English version. I had to wait until the next day to get on the bus at the correct time."

Dialects

Many participants emphasized that translations — even if technically correct — could be hard to understand due to dialect differences. For example, while there is a formal Arabic language, this is often not understood by people who haven't been formally educated. The spoken (and written) versions spoken in the more than 20 countries where Arabic is the official language can differ a lot.

Similarly, the Spanish of Spain and the Spanish of Mexico, or Colombia, or Venezuela, share a foundation but include meaningful differences. This can be a challenge to users. For Mandarin speakers, the difference between Simplified Chinese (from mainland China) and Traditional Chinese (from Taiwan and Hong Kong), means that a reader of one can only read about 60% of the other.

Methodology and process

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in 2023 and 2024. Test participants were screened to ensure they had little to no English-language proficiency. Most participants were identified by working through local organizations, such as a library or a community center; some were recruited by word-of-mouth referrals.

Informed consent was secured from all participants, who were also compensated per General Services Administration (GSA) guidelines. Care was taken to ensure an ethical, trauma-informed approach with this vulnerable population. All responses have been pseudonymized.

Most of the interviews were conducted in person at the partner organization's site. A few were conducted remotely. Interviewees were asked to describe their search behavior and were shown a series of mock-ups.

Demographic information

Locations of origin

Age of participants

Hypotheses

Hypotheses were developed and refined with stakeholders and subject matter experts. Each hypothesis was mapped to user questions and artifacts. Questions were tailored to be linguistically and culturally appropriate. Responses were mapped to hypotheses.

Primary hypotheses and the summary findings are listed below:

| Hypotheses | Summary findings |

|---|---|

| Monolingual users whose preferred language reads left-to-right look for language options in the upper right of the header navigation. | Monolingual test participants looked for the language selector in the upper right. They did not distinguish between placement in the nav or in the utility bar. |

| Monolingual users whose preferred language reads right-to-left look for language options in the upper left of the header navigation. | Monolingual Arabic test participants are accustomed to looking in the upper right for the language selector, despite Arabic-first sites placing it in the upper left. |

| Monolingual users are more likely to find translated content when they see a call to action (CTA) in their native language. | All test participants preferred the language selector to be in their native language. |

| Monolingual users look for a link titled "Languages" (or something similar) to find the language selector. | Most test participants were able to recognize the term "Languages," even though they could not read English. For most participants, "Languages" communicated where they would find translated content. Other terms were tested, including "Translated." "Translated" communicated that a machine translation would be conducted on click. |

| Monolingual users find translated content more easily if there is an icon. | An icon alone did not communicate "translated content" to users. A number of different icons were tested, including [insert graphics]. An icon increased visibility of the button when paired with "Languages." |

| Monolingual users find translated content more easily if there is an animation such as at LEP.gov. | Test participants agreed that the animation increased the visibility of the language selector, but found the interaction confusing. Many felt they had to wait until their language "came around again" to select it. |

| Monolingual users look for a dropdown menu to choose their preferred language. | Test participants confirmed that they look for a dropdown to select their language. On the provided mockups, they noted that they expected a dropdown affordance. Without the affordance they were confused about whether it was a dropdown menu or a link to another page. |

| Monolingual users find the link more easily if the dropdown menu lists their choice in their native language. | All test participants confirmed that the dropdown menu should list their language selection in their native language. Many Arabic test participants noted that the correct term for the language should be Arabi (عربي) rather than العربية which means "The Arabic language." |

| Monolingual users are more likely to find content if there is an in-page link in addition to the CTA in the header. | Test participants said they do not scroll to look for the link to the language selector. All test participants accessed the internet almost exclusively on their phone, and if the language selector was not at the top, they assumed there was not translated content. In general, test participants had a low level of technological sophistication; some participants acknowledged looking under "the three lines" (mobile or hamburger menu) for the language selector, but not all. |

| Monolingual users prefer to have sites alert them to the availability of content in their preferred language, rather than present the content by default. | Test participants were almost unanimous in disliking alerts and pop-ups. They indicated that they associated them with scams and would not click on them. |

| Monolingual users prefer to have sites present content in their preferred language by default using their paradata. | Test participant feedback was mixed on this, though on the balance they did not prefer to have content in their language presented by default. They were suspicious that content in their preferred language was a subset of the English-language content or was outdated or inaccurate, and wanted to be able to reference English-language content (or bad auto-translations of English-language content). A number of test participants said they wanted to be in control of their digital experience. |

| Monolingual users want to be alerted when the content available in their preferred language is only a subset of available content. | Test participants concurred that this would be helpful, but were uncertain how this should be done. They also acknowledged that they were used to only having a subset of content available, so much so that they expected it. |

| Monolingual users prefer to be alerted when a link or CTA will take them from their preferred language to English. | Test participants agreed that this would be helpful, but also indicated that this is such a frequent occurrence that it is an expectation. |

Conventions

Throughout the report we refer to "speakers" of specific languages. When they are interacting with government sites they are actually "readers." In a couple of cases with the Spanish-language participants it appeared that literacy level was an issue. It is a good reminder that speakers of languages other than English require the same literacy and accessibility support as English-language speakers.

Disclaimer

Mentions of and links to nongovernmental sites and sources are made for educational purposes only, and do not represent an endorsement of the organization by the General Services Administration. The General Services Administration does not assume any responsibility for the content, operation, or policies of other entities' websites.

About 10x

10x is an investment program that takes ideas submitted by federal employees and turns them into technology projects that improve how the government delivers excellence for the public. 10x is a part of GSA's Technology Transformation Services (TTS) division. TTS applies modern methodologies and technologies to improve the lives of the public and public servants.

Tag: Research-findings